What are we aiming to do

hISTROX is a three-year project (2024-27) funded by the Leverhulme Trust which continues and develops our pilot project, ISTROX, on the Istro-Romanian language and its speakers. This new project aims to publish an accessible History of Istro-Romanian, meant not only at specialists—such as linguists, historians, or ethnographers—but also the general public including, community members and their descendants in the diaspora. This will be the first historical treatment of the language published in English, unlike previous works which are mostly in Romanian or Croatian. We hope that this will increase the accessibility of our research to an international readership.

The first part of our work/volume will deal with the external history of the language. By this we mean the history of the language in relation to the community that speaks it, the places in which it has been spoken, other communities with which the language and its speakers have come into contact, the uses to which it has been put, and the attitudes of speakers and non-speakers towards it. For the mid-to-late-twentieth-century we will invite surviving speakers to reflect on their lived experience of the history of the language and the community. We have already made contact with second and third generation members of the community from Australia and the United States, who have helped us expand our contacts and expressed interest in staying in touch. A nucleus of descendants of Istro-Romanian speakers worldwide is still interested in their heritage. Interaction with them will help us find out about their knowledge of the language and, in time, let them become co-creators of a new body of knowledge about the language.

Among the many questions we want to address are:

•Where did Istro-Romanian originate, and where was it spoken before it arrived in Istria?

•How, and why, have the numbers of speakers declined since the 1960s, both in Croatia and in the diaspora?

•How, where, and when do speakers still use Istro-Romanian to each other?

•What is the nature of modern Istro-Romanian bilingualism?

The second part of the History will look at the internal history of the language. This means that we will be looking at the development of its grammar, sounds, and words, particularly emphasizing the effects of prolonged contact with Croatian. Again, an important element will be our own fieldwork and our online work with speakers and community. Some examples of the many linguistic topics we will look at are:

•‘Aspect-marking’ in the verb. This is a major characteristic of verb morphology in Slavonic languages but not in Romance. The fact that it exists in a Romance language such as Istro-Romanian it is clearly due to Croatian influence, but how has it been adopted from Croatian and what is the result?

• Plural marking in nouns. The distinction between singular and plural in nouns has been extensively lost in Istro-Romanian. How did this happen, and what are the consequences for the grammar overall?

• ‘Alternating gender’. It is a famous characteristic of Romanian and its immediate sisters like Istro-Romanian that they have, or once had, very large numbers of nouns that have masculine gender in the singular but change that gender to feminine in the plural. This peculiar phenomenon has long been in retreat in Istro-Romanian, but its retreat has been complex. What happened and why?

• Numerals. Istro-Romanian has borrowed numerals from Croatian. Numerals and numeral structure from both languages sometimes exist side-by-side in Istro-Romanian, but how and why? Their coexistence even gives rise to a unique kind of ‘numerative’ form of noun plural.

Our methods are mixture of the traditional and the innovative. This is the first attempt to narrate the ‘external’ history of this speech community by drawing directly on the testimony and life-experiences of its surviving members and their descendants. We are interested in surviving fluent and semi-fluent speakers and their descendants (even if they no longer speak the language). Through our earlier projects we have already laid the foundations of an environment open not only to speakers of the language but also to their relatives who may no longer speak it, both in Croatia and in the diasporic communities.

As a response to the fact that the speakers of Vlaški and of Žejanski are scattered across the world, in August 2020 we launched a community-sourcing site on the online platform Zooniverse. We have uploaded audio clips taken from the recordings made by Tony Hurren during the 1960s and invited speakers of the language to listen to the recordings and perform some simple tasks in order to help us understand more not just about the language but about the speakers themselves. Even though the technology was at first unfamiliar for older speakers, these contributions have helped us expand our pool of contacts among Istro-Romanians in Croatia and the diaspora as a bridge towards the current phase of the project. Today our Zooniverse site – which remains open to contributions – is an environment where contributors already feel welcome to keep in touch with us, or share thoughts about the project and to which they will continue to be encouraged to contribute.

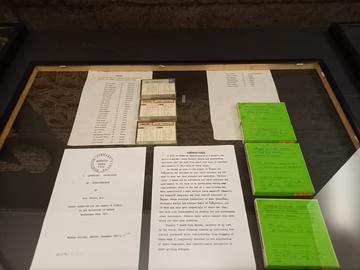

To understand the history of Istro-Romanian and its speakers until the Second World War we will draw on the many written sources that we have, beginning with the observations made mainly by linguists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For earlier centuries, we will look at a range of historical and diplomatic documents.

For the period since the Second World War, talking to surviving members of the community for their first-hand experiences of relocation and migration will play an important role. By using photographs, sound recordings, and other archival materials, we hope to stimulate memories and reflexions to understand the forces that compelled community members to leave their villages and how they maintained their identity after that.

All this material will form the basis of a further product of our History, namely an ‘e-corpus’, comprising audio, photographic, and archive material, documenting the history of language use in Istria and the diasporic communities. The corpus has three goals:

1) to gather as much linguistically, ethnographically, socially, and historically relevant material as possible within the constraints of our work on the History

2) to capture current language use, not just in spontaneous speech and conversation, but also through modern means of communication—comparing what we gather with Hurren’s observations from the 1960s

3) to make fluent or semi-fluent speakers become an active part of research which is carried out for and with them.